1 Power and Speed, printed in Lone Hand 1911

Boys Own beginnings: trains, boats and planes

Unless you’re beat, you’re bound to win. (Marcus Aurelius)

With this quote up-front as a personal motto Captain Frank Hurley begins Argonauts of the South a vivid and fast-paced story of his adventures as official photographer to the Australasian Antarctic Expedition (1911-14) under Dr (later Sir) Douglas Mawson and the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition (1914-17) led by Sir Ernest Shackleton.

In 1919 Hurley had been awarded the Polar medal and clasp for his spirit, courage and efforts as a team member as well as marvelous films and photographs of the Antarctic expeditions. His Antarctic book was published in a handsome edition by New York publisher George Putnam in 1925.1

|

|

Hurley, by origin a working-class boy from Australia with little education, was then on top of the world himself.

He had gone to the Antarctic as J.F. Hurley, the Sydney postcard photographer but returned as Frank Hurley adventurer, showman and cinematographerand from WWI–WWII would be known to the public as Captain Hurley, traveller, author, cinematographer and broadcaster.

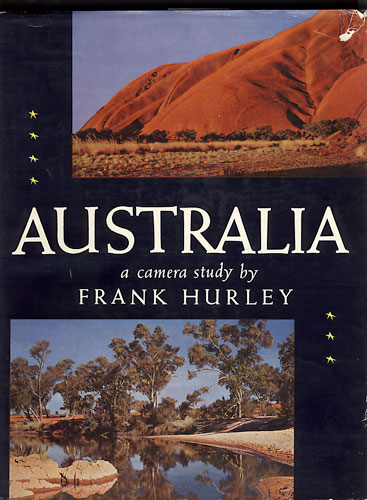

In his last decades Hurley OBE would be best known as the ‘picture-laureate’ of post-war prosperity through his scenic Australiana books, cards and calendars.

In 1925 in the midst of the jazz age Hurley was securely elevated to the ranks of the pre-war heroes of Empire. He was however, always the astute businessman feeling the pulse of the public and adopting new technology but was not particularly interested in modern culture.

Back in Australia his beautiful Anglo-French wife and four children lived in a large English manor style house he named Stonehenge which had magic panoramic views of Sydney Harbour. He had already built elaborate rockeries, pools, arches and gardens as he would in all his later houses.

He was internationally known as the Australian whose dramatic stills and films, as well as his lively illustrated talks and screenings with commentary, had salvaged the finances of both his Antarctic expeditions.

He had also made an impact at home and in Europe with his World War One photographs and films and had taken to the air in flying machines and made a film of fellow Australians’ Ross and Keith Smith’s pioneer flight from London to Sydney in 1919

Most recently, following expeditions to New Guinea between 1920-23, Hurley had appeared as an explorer in his own right through his film-lecture tours in America and England. Hurley was the first Australian cinematographer and photographer to earn a significant and broad public reputation outside his country.

Pearls and Savages, Hurley’s first book had been rushed into print just the year before Argonauts came out by George Putnam to capitalize on the interest in Hurley’s New Guinea experiences.

As Argonauts was being released in New York, Hurley was back in New Guinea shooting two feature films, Jungle Woman and Hound of the Deep, which were released the following year. Hurley’s books were best sellers but his foray into feature movies was not quite so successful.

The 1920s were the peak years of Hurley’s international reputation; the glorious expeditions were not to be repeated and Hollywood didn't call.2

Hurley’s catchy title Argonauts of the South linked the heroes of Greek mythology with his modern cohort of Antarctic explorers. It was also the first public account of Hurley’s own odyssey taken back to when he started out at 13 by running away from school and home. |

| 2 Frank Hurley Circa 1911 |

|

|

|

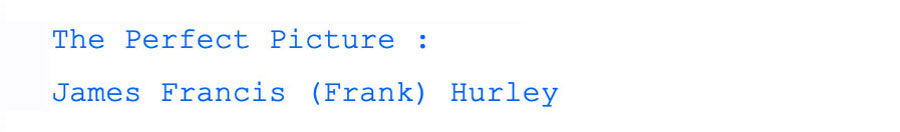

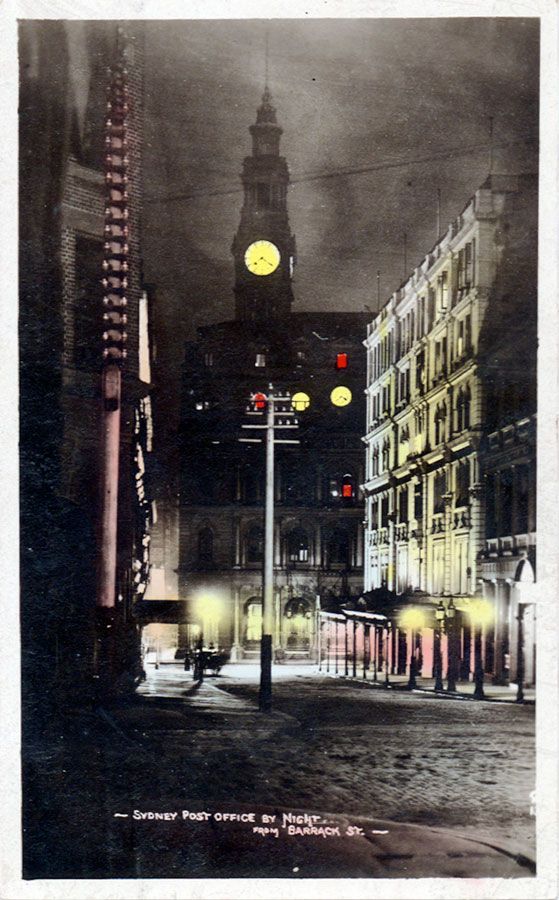

3 Sydney Post Office by night from Barrack Stree,

Cave & Hurley postcard Circa 1908 |

|

It was a story Hurley told with varying and contradictory details over his lifetime. Hurley may not have shone at school but loved gadgets and worked well with his giant hands. He could compose doggerel and was by all accounts a natural orator and entertainer in front of an audience but was essentially a loner who preferred to be outdoors. He was uneasy with social life and close to few people.

His twin daughters recall how he wanted everything to be perfect – including them, but also instilled in them strength and independence.3

They tell how he kept an audience in thrall with no need of a microphone and how at Christmas he would recite from memory, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, Samuel Coleridge’s romantic poem inspired by polar exploration.4

Hurley’s creation of a personal legend points to a need to establish that he was self-made and pre-destined to be famous. Quite early on he also tended to take a few years off his age in published reports, leading to a birth year of 1887 then 1890.5

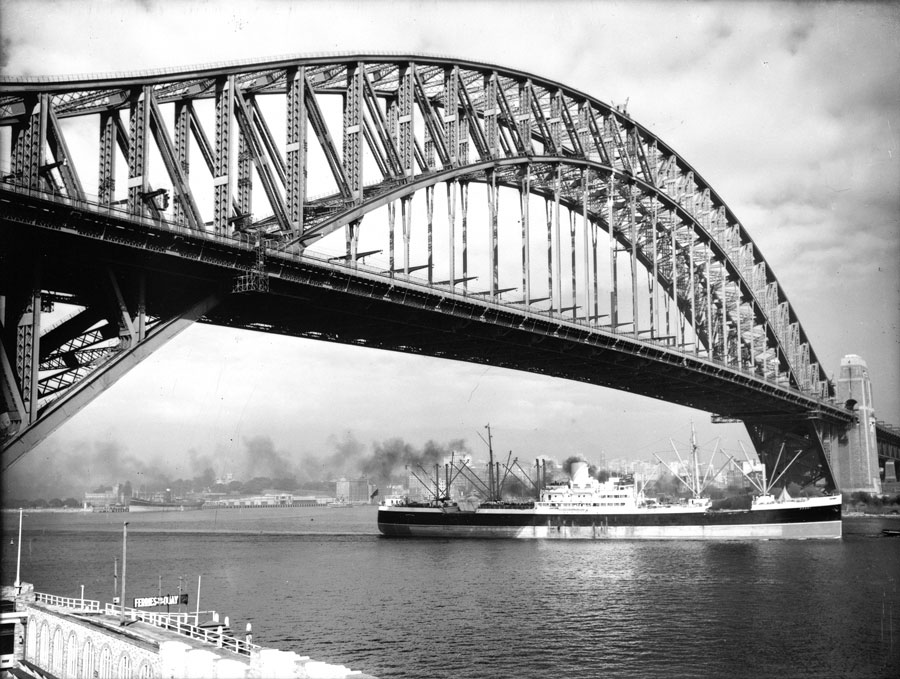

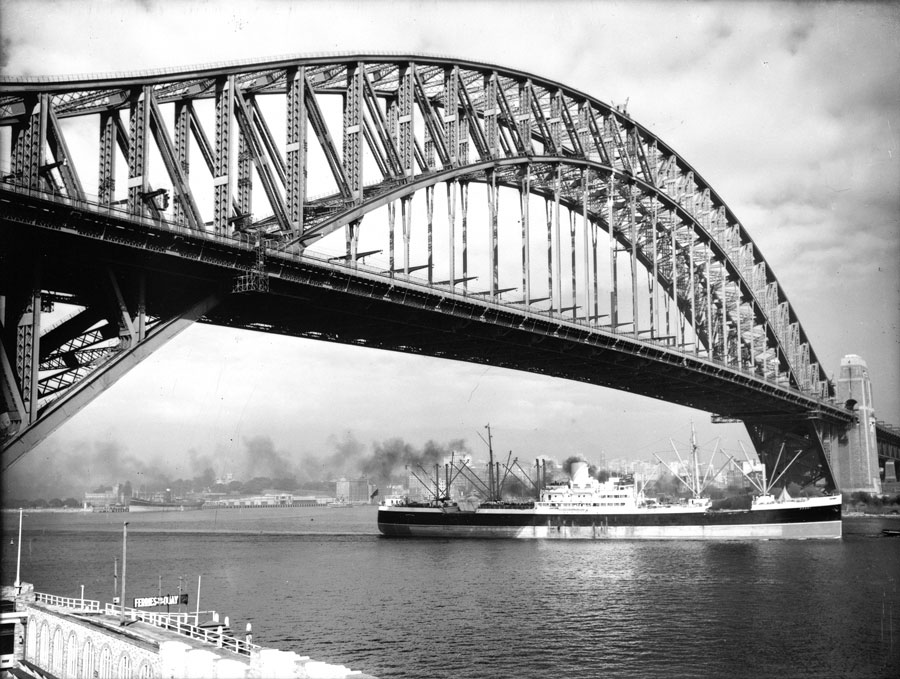

4 Sydney Harbour Bridge from Circular Quay Circa 1960

Early Hurley

James Francis Hurley was however, born in Sydney on 15 October 1885 in the inner city suburb of Glebe. By the 1880s The Glebe was densely built up with a mix of workers’ cottages, multi-story terrace houses as well as Italianate mansions for the more affluent middle class families. The Hurleys lived in small cottages at several locations.

Frank was the third of five children; his father, Edward Harrison Hurley, came from Lancashire and was evidently born in England although the family appear to have been Irish-Catholic by origin. Many Hurley names appear in connection with mining in western New South Wales. Hurley senior had trained in Australia as a newspaper typesetter and by 1885 worked in the New South Wales Government Printing Office.

The Hurley family appear not to have much made much of their Irish origins or to have been active Catholics. Hurley senior was evidently articulate and was active in union affairs serving terms as secretary of the New South Wales Typographers Association.

He evidently had ambitions that Frank might rise further into the professions. Frank’s mother Margaret Bouffier’s family were vintners from Alsace Lorraine who had immigrated to Cessnock a mining area in rural New South Wales.

As a boy peering out his attic window on torpid evenings, Frank Hurley dreamed, not of upward mobility, but of adventures at sea or beyond the distant Blue Mountains to the west of Sydney. School did not appeal and he did not attend regularly but may well have picked up his thirst for adventure from children's editions of poems and novels then in vogue in the school rooms.

These colloquial versions mixed romanticism with tales of the courage, honour and self-sacrifice required of those fortunate to be part of the British Empire. And so one day in his telling in 1898, fearing the consequences of one of his regular truanting escapades, young Frank quit his school and hopped a freight train going to the mountains.6

After some adventures he ended up in the mining town of Lithgow 140 kilometres west of Sydney where he quickly found work as an assistant fitter in an ironworks. Never, the complete rebel, Hurley reports he immediately wrote to his parents and received a blessing to stay on. Hurley repeats his father’s advice ‘Let- Find a way or Make one - be ever your motto’ in various accounts of his life story.7

Frank enjoyed the factory work and at some point the city-boy was also introduced to the pleasures bushwalking and possibly amateur photography.

All his life Hurley was to have the knack of attracting support and assistance an outcome of his plucky manner, determined spirit and gift of the gab.

He was big, strong and good looking with bright blue eyes and a full head of dark curly hair.

After a couple of years in Lithgow, Hurley was back in the city with a vague plan to go to sea as an engineer. He had various jobs and undertook technical courses at night. Probably around 1904 while in employment with the Telegraph Department, and learning electrical instrument work, Frank was introduced to the magic of making photographs:

From the time I first gazed wonderingly at the miracle of chemical reaction on the latent image during the process of development, I knew I had found my real work, and a key, could I but become its master, that would perhaps unlock the portals of the undiscovered World.8

The Professional Photographer

Such conversions were common after the turn of the century when do-it-yourself photography was booming and the postcard craze was underway bringing the medium into every home. Hurley sought out people who could help him learn the techniques. His closest friend was a young man of his own age, Henri Mallard, an Australian-born child of French parents who worked at Harrington's Pty. Ltd a large photographic suppliers in Sydney.

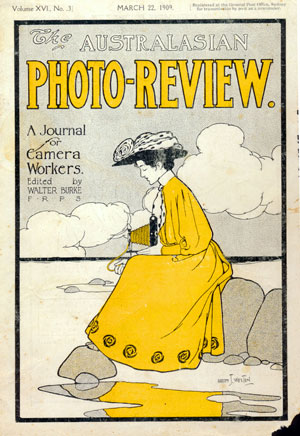

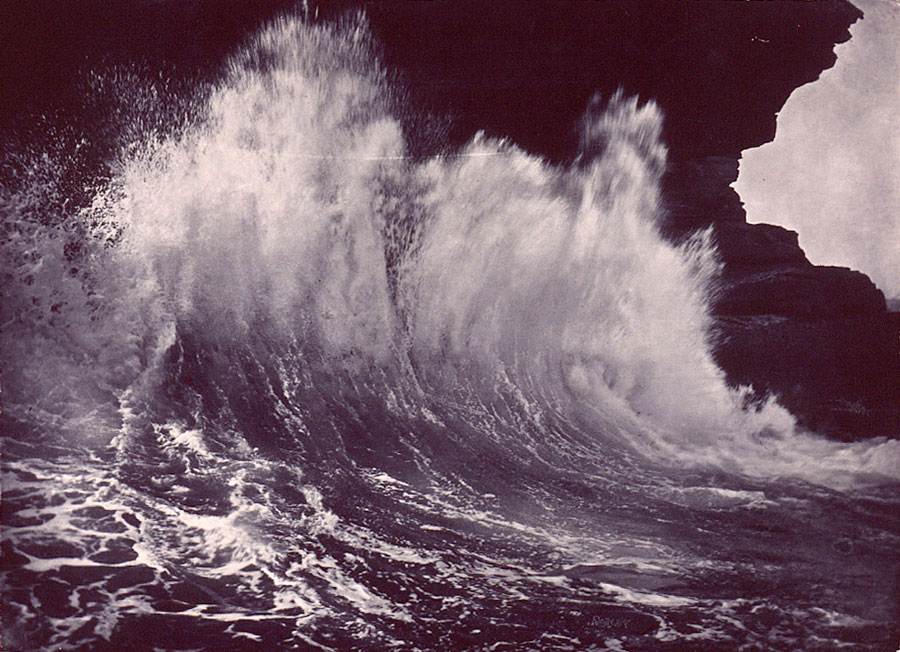

Mallard had taken up photography in 1904. The two young enthusiasts weekends were taken up with excursions and developing their photographs in a darkroom Hurley installed at home in Glebe. Frank’s first picture to be published appeared in the Australasian Photo-Review of June 21, 1905. It was a close-up image of a huge wave breaking against a cliff face at Manly, a hard subject to get with the slow speed emulsions of the day and hazardous at any time.

Over the next few years Hurley would become known for dramatic photographs which involved some risk and daring or technical challenge to obtain.

Hurley’s path from amateur to professional was rapid. The postcard business was exploding around Sydney, and by 1908 Hurley, with financial help from his parents was in partnership with card producer Henry Cave for whom he may already have worked as an employee.

The next couple of years passed with long hours of work filling orders and creating ever more novelties in a saturated market. Hurley regaled readers of the Australian magazines with stories of his exploits to get pictures of waves and trains steaming out of tunnels – losing several cameras in the process.

The company’s Power & Steam series were best sellers around 1910.9

Cave and Hurley cards were often dramatic with subjects silhouetted against twilight scenes or sunsets or bright lights of the city at night. Some of the cards were hand-coloured. Telling the story of how he got his pictures was always an important part of the process of Hurley’s lectures and interviews and wherein he learned his first showmanship. |

|

5 Cover of APR, March 1910 |

|

|

|

6 The Steel Track, Sydney,

postcard by JFH (James Francis Hurley) Circa 1910 |

|

7 Driving Spray, Sydney

Cave and Hurley postcard, Circa 1910 |

8 Ashfield Camera Club circa 1910

Hurley in white shoes to (our) right of album in front row; with (possibly) Mallard with dogs to the left of album.

By 1910 Hurley was the full professional mentor, delivering talks to the New South Wales Photographic Society on such technical challenges as photography at night and combination printing.10

In 1910 he was a founder member of the Ashfield Camera Club with Mallard and Norman Deck, another friend.

Hurley also had a one-person show at the Kodak showroom the same year. In 1911 he was on the committee for the older established New South Wales Photographic Society’s big interstate Salon. In five years he had risen from one of thousands of amateurs to their teacher and judge.

At this time Hurley‘s work was more dramatic but not unlike that of his Pictorialist contemporaries and he made one or two images which followed their fondness for soft-focus impressionistic nocturnes but his approach to the ‘fuzzy-wuzzies’ as the art photographers were called, was limited.

9 Safe at anchor, 1910

10 The Last Break, Sydney, circa 1910

His work adopted the dramatic lighting effects and ‘story’ elements of Pictorialism but Hurley’s greater debt was to the methods of the commercial postcard view involving an arsenal of tricks for improving the printed image by adding, subtracting or heightening of details, tones and effects.

The postcard trade itself, like the growing use of photographs in newspapers and magazines in the first decade of the century, was a direct lesson in what went down well with the public. Cards either sold in tens of thousands – or were duds.

Original print and photogravure postcard prints were the last major phase of the views trade of the late 19th century in which millions of finely detailed and majestic albumen prints had been sold to be put in albums as mementos and testimonials to colonial progress. Illustrated papers and magazines would take over from cards as the most populous form of photograph even before World War One. The proliferation of these photographic images also increased the competition and need to create an attention-grabbing image.

Hurley must have been feeling quite pleased with his situation by 1910 but at this point the postcard business fell into sharp recession. Fate as he would see it - while putting an obstacle in his path, would also lead to him to future adventures.

Perhaps because of business woes Henry Cave fell ill (or may have absconded) and Hurley was forced to sack staff and relocate nearby to smaller rooms but was still left with serious debt to the Kodak dealership and Harrington’s for supplies. His father had died prematurely in 1907 and Hurley missed his support.

In Argonauts of the South, Hurley describes how one night after climbing up the stairs to his premises feeling overwhelmed by his misfortune he saw ‘a silvery beam that shone through a window and flooded the stairway with light’. Whereon he felt a renewal of energy to carry on and ‘turn the corner’.

He goes onto to relate how, soon after, he was off to the Antarctic as an official expedition photographer.11

It was a scene worthy of a movie script but also a clue to meanings he saw in the cloudburst and beams of light which were to figure so much in his work.

The Antarctic

Dr Douglas Mawson, head of the Geology Department at the university in Adelaide, South Australia, was on a brief visit to Sydney preparing for the first Australian scientific expedition to the Antarctic. He was consulting with Professor T. Edgeworth David his former professor and companion on the British Antarctic Expedition (1907-9) in the Nimrod under Shackleton.

Mawson and David and their companions had already both taken photographs in the Antarctic but Professor David, especially skilled in stereophotography, was urging the employment of a professional.

Hurley was one of a number of possible candidates. However, rather than rely on a brief meeting at the Central railway station in Sydney, Hurley arranged to join Dr Mawson in his carriage as he was departing for Melbourne and then travelled the route for about two hours south to the stop at Moss Vale.

Mawson cabled Hurley two days later from Adelaide ‘You are accepted’. Mawson later said he saw Hurley’s little stunt as initiative and it that earned him the position as much as his evident technical skills and fitness.12

Mawson was deliberately choosing young fit Australians and New Zealanders for both the scientific positions as well as crew for his expedition. Later Hurley’s friend Henri Mallard revealed that he had been first choice but when approached by Professor David declined.

He put Hurley’s name forward instead and then arranged with Harrington’s and Kodak to write off Hurley’s debts. Kodak took over Hurley’s premises as a same-day printing service. David gave Hurley his stereocamera.13

Mallard had to perform one more favour. He made sure that Frank quickly learnt how to use a movie camera. They went out on the streets and then developed the film. Coming out of the darkroom he said ‘Look Mal, everyone a perfect picture’. Frank Hurley, a young man in his mid twenties, was now poised to start his life as an adventurer as both a still and cinema photographer.14

Mawson had signed up Hurley for the fee of £300 per year plus the best cameras available within Australia at the time. Not surprisingly Kodak in Sydney supplied the equipment. On 2nd December 1911, Mawson and his team set sail from Hobart, Tasmania, aboard the Aurora.

A brief call at Macquarie Island to deposit a small party and equipment was complicated by Hurley pulling a stunt to gain extra time to get a series of pictures of the wild life.15 The journey south was difficult, with the ship having to deal with pack-ice. However, after two weeks of the icy encounters, the Aurora found safe haven on Adelie Land in a bay that Mawson was to call Commonwealth Bay.

The Aurora moved on to West Base, 1600 kilometres along the coast. The party camped down at the Winter Quarters in the two wooden huts they had built. Hurley’s photographic and technical skills were now being constantly put to the test under extreme conditions. Not only his skills as a fitter and electrician but an Australian tradition of ‘making do’ were demonstrated on many occasions.

Hurley may have kept diaries since childhood but he certainly began meticulous records on the Mawson expedition. He also had a flair for word pictures; thus in Argonauts, Hurley was able to be very precise about his experiences.

In describing the setting for one of his most famous images, the penguins on the Macquarie Island he could write on page 22: Picture an irregular –shaped basin of deep green water with green jagged peaks rising to cloudy mists in the sky above, and a little strip of grey shingly beach, crammed with penguins’

11 Penguins on the beach at the Nuggets with wreck of the Gratitude, Circa 1914

In late spring, Mawson sent out a number of expeditions. One of these involved Hurley who selected not only for his photographic skills but more importantly for his positive attitude, strength and energies. His spirit was soon tested. On 10th November 1912, Mawson sent Hurley, Badgett and Webb sledging over the Antarctic Plateau to reach the south magnetic pole and make scientific readings.

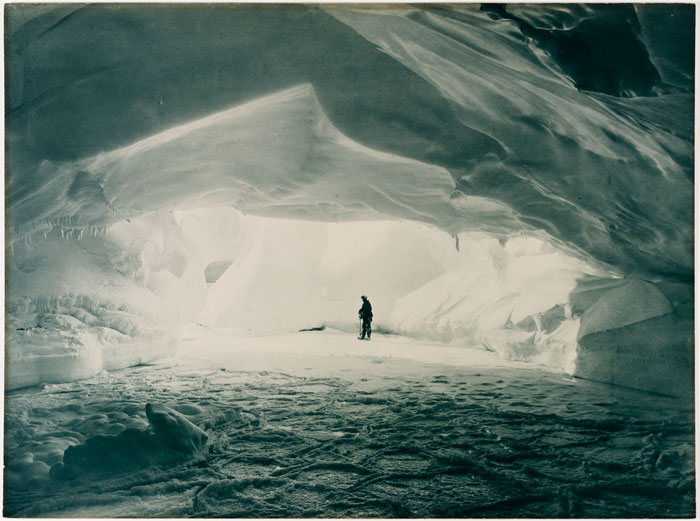

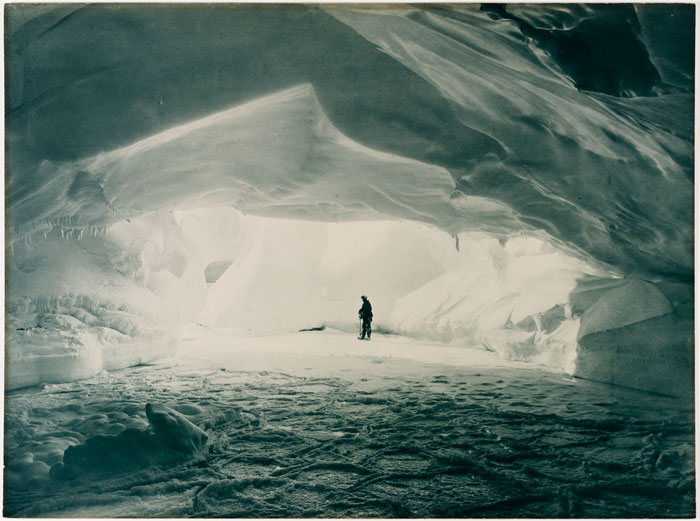

The team worked hard through all sorts of conditions, but by 21st December, 80 kilometres from the Pole, they turned back. Conditions and their situation deteriorated until a real threat of death existed. When all seemed lost, the weather suddenly cleared and they found themselves looking at the sea and Commonwealth Bay. Again Hurley records in Argonauts on page 90 how at the darkest moment:

A strange feeling came over me, infinitely comforting. Some indefinable force seemed to be beside me and guiding me on. In a state of high exaltation I knew we were going to win through. Our jaded bodies, still and frostbitten, rebelled, but WILL won. |

|

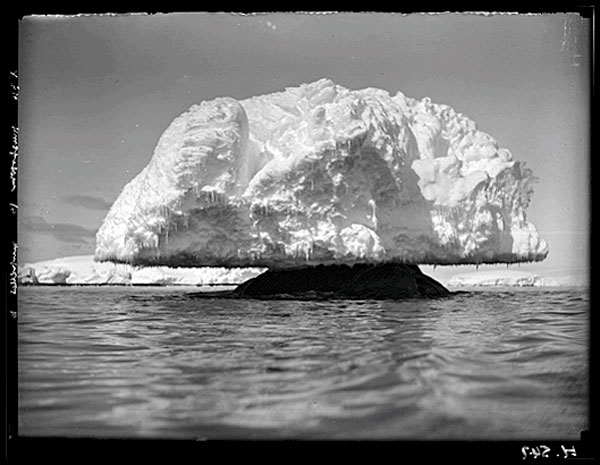

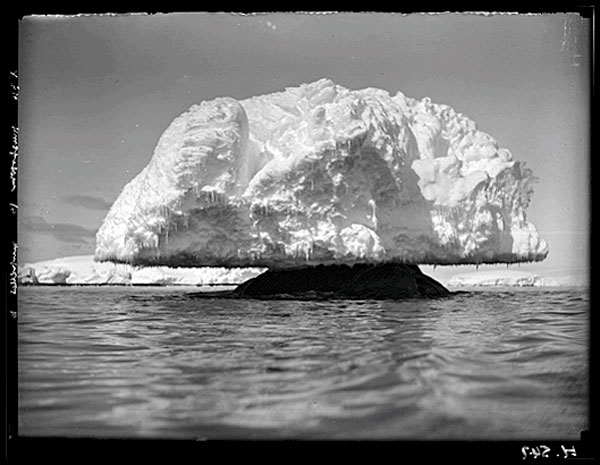

12 Ice, Antartica, Circa 1914-1917 |

Hurley was not religious and skeptical of the Church and many social conventions but commented on how the Antarctic experience tended to instill faith. Soon it was time to depart and the Aurora was readied before the onset of the winter blizzards. However, while most of the other expedition teams had returned, Mawson and his team had not. As the pack-ice was closing in, the decision was made to set sail for Australia, leaving a small team to join Mawson when he returned.

His companions Lieutenant B.E.S. Ninnis and Swiss Xavier Mertz had perished and Mawson only narrowly escaped death because he found a food depot and directions left by Hurley and a search team. Bad weather delayed Mawson further and the pick-up ship had to sail. He returned alone and very ill and poisoned from eating the livers of the dog team.

Mawson and a few of the expedition members had to spend another winter awaiting the return of the Aurora.

Hurley did not stay behind and with the 15 months journey behind him, returned to Hobart. He was now a celebrity, both as an adventurer and photographer.

The photographic fraternity would listen in awe as they had to the earlier descriptions of his efforts to hang off girders to capture trains at full belt. Back in Sydney, he had to work long hours putting together a film and lectures to raise finances to assist the Aurora's return for Mawson. Home of the Blizzard premiered in Sydney later that year.

Hurley further developed his style of giving lectures into a polished showmanship as he stood by the screen providing commentary for the film or his lantern slides some of which were in colour, being from Paget colour plates. Meanwhile, he was commissioned by a shipping line to do a travelogue on the island of Java, then a major port for ships en route to Australia. He set out for his first trip to the tropics together with new adventures, and of course, daring feats in order to gain images. 16

13 Antartica photograph (untitled)

14 Antartica photograph (untitled)

On 19th November, Hurley rejoined the Aurora for the voyage to pick up Mawson. He spent ten days on Adelie Land photographing flora and fauna. This time Hurley returned with Mawson to Adelaide where Mawson now received his hero’s welcome as a native son.17

However, as all the images belonged to the expedition, Hurley found himself unemployed and with little stock with which to advance his career. Again it was a case of luck and someone else coming to the rescue. A pioneer of arduous overland motoring, roving freelance reporter and cinematographer, Francis Birtles, approached Hurley to come on a motor car journey to the far north of the country then a largely unfamiliar region that formed the ‘bush’ and ‘outback’ of Australia. The roads and conditions had not much improved since they were made in the late 19th century.

Birtles was skilled at promoting his endeavours and was able to gain the support of the newspapers to pay for the journey. He also gained a commission from Australasian Films Ltd. (later Cinesound) to film the Aboriginal people and outback stations. The pair left in style from the Sydney showgrounds on 14th April 1914 on the four months journey over thousands of miles through tropical Queensland and the Northern Territory.

They returned to a welcome in Martin Place in central Sydney four months later. Birtles released the commissioned film as Into Australia’s unknown in 1915. Hurley retained many negatives of striking and beautiful images, especially of Aboriginal life, and used these throughout his later exhibitions and publications.

15 Child and puppy, northern Queensland. 1914

Men wanted: for hazardous journey. Small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success. Sir Ernest Shackleton18

This advertisement in full Boy’s own paper style appeared, in a London newspaper in 1913, recruiting members for the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition which was the dream of Irish explorer, Sir Ernest Shackleton. He planned to be the first to cross Antarctica ice-cap on foot. The advertisements attracted an overwhelming response including it seems an application by Hurley.19

However, he also told another version in which Shackleton’s backers aware of the critical role Hurley’s films and stills had had in recouping costs of the Mawson expedition, insisted that Shacklelton contact him and appoint the Australian. In this version Hurley tells how he was camped one evening with Birtles miles from anywhere in Queensland, when an Aboriginal runner delivered Shackleton's cable and then ran back the long distance to deliver his acceptance to the Burketown telegraph station. Birtles then drove Hurley all the way back to Sydney.

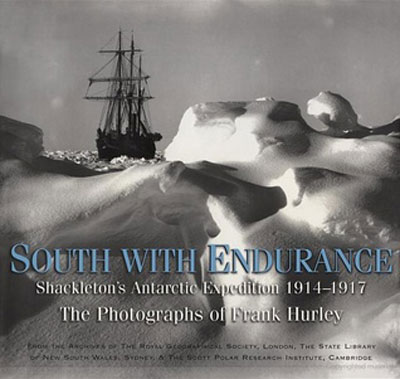

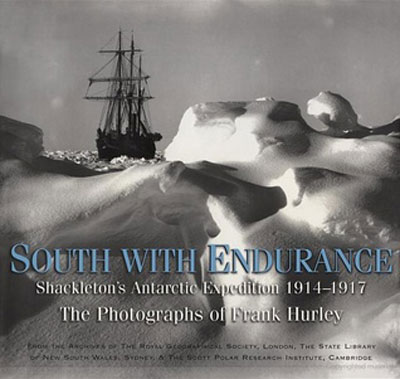

War had been declared and Hurley sailed from Sydney on one of the last ships to cross the Pacific to join the Endurance in Buenos Aires reaching there in mid – October at the same time as Shackleton.20 Ahead lay a 22-month ordeal with the journey a failure in even starting on the immediate goals but to become as heroic and adventurous as promised in the recruitments.

The Antarctic continent was not even to be landed. Most of the time was to be spent on ice. The ship’s name would be uncannily apt. Their story of endurance was to enter the history books as one of extraordinary and inspiring courage and determination with Hurley and his images to figure as part of the aura of noble achievement, rather than failure.21

Hurley and Shackleton met in Buenos Aires in mid-October, 1914. Hurley had been hired on a salary basis, with no rights in the pictures. By the time the Endurance departed Buenos Aires for South Georgia, ten days later, Hurley had apparently changed his mind. According to the diary of Thomas Hans Orde-Lees Hurley, ‘practically put a pistol to Shackleton’s head when leaving Buenos Aires, saying he did not come for salary' and secured a 25% share in the motion picture rights.22

What followed was the disaster of the ship being imprisoned in the ice-pack. During this time of being stuck on the floating ice, Hurley had little opportunity for photography due to the weather. However, on the 27th August, he did manage to capture the now famous flash photograph of the Endurance. During this period he also carried a number of successful experiments in colour photography.

In mid October when the ship was finally being crushed, Hurley spent three days on the ice with his movie camera waiting for the end. It came quickly and Hurley got his film.

They evacuated, with Hurley being ordered to leave all film, equipment and even the exposed plates. Hurley however, snuck back and retrieved the glass plates and film from mushy ice water inside the shipwreck. He was caught out by Shackleton but a compromise was agreed to and Hurley saved some 120 glass plate negatives, the already developed cinema film and one small Kodak camera and 3 rolls of unexposed film. He smashed and left behind about 400 plates.

Hurley and most of the crew then had to await rescue on Elephant Island following Shackleton's now famous voyage to South Georgia in the James Caird. More than anything Shackleton’s 800 mile voyage captured the public imagination. After three attempts, Shackleton arrived in a ship to collect his marooned but still surviving crew.

16 The James Caird sets out from Elephant Island, Frank Hurley, 1914-1917

London

The leader, his English crew and Hurley arrived back in London on 11th November 1916. This was Hurley’s first visit to the UK. But he found the atmosphere, especially given the slow pace of the war in Europe, to be depressive.

On December 5th 1916, some of Hurley’s photographs were used by the Daily Mirror in an article that highlighted the heroism involved in the rescue of Shackleton’s crew. Their spirit was now recruited to the war effort. If Hurley did read the rousing poems of courage and endurance for the sake of Empire that were so popular in his youth he now had the satisfaction of having lived out every school boys dream.

However Shackleton’s agents were not able to use the saved film without the addition of some more images. So Hurley organised to return to South Georgia to gather more images and footage of birds, animals and the landscape. Just months since the rescue, on the 15th February 1917 Hurley set sail again for South Georgia where, after five weeks work, he succeeded in gathering the images and shooting the film footage required.

He also took 72 Paget colour plates. Thanks to Hurley's efforts the subsequent film release of In the Grip of the Polar Pack-ice, and its overwhelming success enabled Shackleton to clear all financial liabilities for the journey. Hurley was now the equal of British heroes but also hot property to expedition financiers and the media.

It was during the production of the Antarctic photographs that Hurley really branched out in his use of ‘composites’; a process whereby he inserted animals, clouds, whales, people, even the Endurance itself, into selected landscape images to give a better idea of the drama of the occasions. He applied to still photography a mode of production familiar and accepted in film – an art expected to be believable and convincing but not necessarily truthful.

This practice applied to reportage of sacred matters such as exploration and matters of national honour, would complicate Hurley’s historical assessment as a photographer and expeditionary.

He was never to ascribe to the documentary truth ideals which became a mission for a later generation of photographers and filmmakers. His alliance was not to professional peers or academics but to the reception of his work by the public.

17 Out in the Blizzard, Winter Quarters, Main Base, Cape Denison, Adelie Land, 1912

The War was into its third year by the time Hurley was back in England from Antarctica. It was a cold and wet winter and the war was not going well for the allies. The battle fields were mud. The army was now looking for positive propaganda from the journalists and their newspapers.

Hurley, or rather Captain Hurley23, now an official photographer for the Australian army, arrived in Flanders August joining Lieutenant Hubert Wilkins, A.F.C. (later Sir) Hubert, a remarkable and much decorated explorer, inventor and pilot) also in the photographic unit under Captain (Dr.) C.E.W. Bean, the official war historian whose mission was to record and enshrine the involvement of the Australians in their first major war.

Bean saw his mission in the long perspective of history, not the news of the moment. He insisted on the primacy of accurate documentary records whereas Hurley was focussed on the immediate popular audience and prepared to use whatever means and aesthetic techniques possible to communicate the mud, the bravery, the courage and the unbelievable situations being experienced by the Australian diggers. This meant that Hurley would use composites to engage the public. He complained that the conditions of modern battle could not be conveyed in one negative.

Hurley’s philosophy and method of operation in the field and later in the darkroom clashed with Bean who referred to Hurley’s composites as ‘fakes’.24

The official censor was also causing Hurley much frustration, as most of Hurley work was deemed too realistic for the general public. ‘Our Boys’ were not to be shown in an unpleasant light.

With the summer offensive, the Australians and New Zealanders were to become the spear-head of the campaign in Flanders. His frustrations with senior officers’ orders on what to photograph and the censor’s attitudes continued.

Relief appeared when, on 9th November 1917, he was ordered back to England and to join the Palestine campaign. He arrived in the Middle East in December 1917, after the Australian cavalry had been the victors in major battles.

In the Middle East Hurley was refreshed by the absence of the former controls put on him and with relaxed attitude and informality of the Australian troops. General H.G. (Sir) Chauvel allowed him the use of a band of Light Horse cavalry to re-stage some scenes, even of engagements that had not originally involved the Australian Light Horse. He was in his element in putting together his own form of dramatic tableaux.

The Middle East was not the hell-hole of carnage and slime that was the western front. He also took many Paget plate colour photographs.

18 Australian Light Horseman picking poppies Belah, Palestine 1917

Hurley described Palestine as ‘more Australian, open air and expansive…..It would be a man’s bad luck to be killed here in action’. Many soldiers regarded Palestine as a holiday compared to France. He was soon restless for more action.

At one time, he took to the air with Captain Ross Smith later to make the first London Sydney flight with his brother Keith. 25

Hurley did however, also relax. While in Cairo, he fell in love on sight with a petite raven haired beauty, Antoinette Thierault,26 a young Anglo-French opera singer. She was the daughter of an English Lieutenant Leighton of Calcutta where she had been raised. Despite their language difficulties Antoinette and Frank married on 11 April, it seems after a ten day courtship. The couple spent their honeymoon on the Nile – it was his only known holiday.

Soon Hurley had to leave his bride to go to England in May 1918 where he was to organise the photographic section of the Australian Infantry Force exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London. The exhibition included many art works and 130 photographs, most in beautiful large carbon prints and six composites as huge enlargements. There was a lantern slide projection show of 124 colour Paget plates.

The show was a great success with the public and Hurley was looking forward to taking it back to Australia. When Captain Bean visited the exhibition he disapproved of what he saw as the hijacking of the propaganda for the war effort by Australian soldiers by the prominence of Hurley’s name and images -including on images that were not his.

Bean made sure the Australian tour did not happen. The artificial montage of different negatives and handwork of his composites were identified but not as openly as Hurley implied.27

It has been speculated that Bean may also have been cross as he had had to intervene when it was discovered that Hurley was attempting to smuggle Paget plates for the exhibition out of Flanders without the censor’s approval (this was a very serious offence).

In his war work Hurley had spent relatively little time at the front but long enough to see the carnage and the unprecedented devastation of modern artillery. Identifying always with the public Hurley felt no concern about the preference he shared with them for the moving persuasive rather than strictly factual, image

.

19 The morning after the first battle at Passchendaele, Flanders 1917

Frustrated and not understanding why the exhibition could not go to Australia Hurley got on with alternative paths to his post-war livelihood. Before departure from England he organised rights to show three Antarctic expedition films and a British war movie The Storming of Zeebrugge on his return.

As a civilian Hurley was free to resign and did so on July 11. He left for Australia on 3rd August 1918, relieved to be free of the official shackles but also with permission to make a set of smaller print versions of his exhibition photographs.

He looked forward to being reunited with ‘the best women in the world – my wife and my dear old mater’ who was back home in Glebe, (both of whom, interestingly, had French blood).

20 Antoinette Thierault-Leighton with Captain Frank Hurley at their weddingCairo, April 1918

Civilian life: New Guinea and Independent Film Making

Mr and Mrs Hurley returned to Sydney on Armistice Day, 1918. Frank was first busy setting up in a large house in the affluent harbourside suburb of Vaucluse with spectacular views, befitting his status if not his income, as an explorer and war photographer.

Antoinette Hurley gave birth to twins, Antoinette and Adelie in May 1919.

Hurley commenced showing the films, giving lectures and networking. He tried to garner popular support through the newspapers where he complained about the red-tape which was keeping his London exhibition from an Australian showing.

It was to no avail and Hurley had to be content with exhibiting the smaller prints he had been allowed to make at the KODAK gallery and in magazine articles (the prints eventually went to the Mitchell Library, Sydney). The lecture tours took him across the country and were hard work. However the bank balance grew to be healthy.

Hurley realised that Bean was behind this thwarting of his ambitions. He was also aware that Hubert Wilkins’ bravery in action had earned him a Military Cross. Post-war, Hurley liked to be known as Captain Hurley, in lieu perhaps of what he saw as lack of recognition from the military. He lost the battle of red-tape but won a permanent place in the national memory as his images would come to represent the Great War wherein Australian national identity was often seen as having been tested and forged.

Not by nature a people photographer, Hurley’s often staged images of the diggers in the field, nevertheless, asserted the value and experience of the troops rather than the generals and the mere facts of battles and medals and remain the most popular images reproduced from this important period.

In 1920 Hurley joined up again with Ross Smith, this time with his brother Keith, when they landed in Charleville, in northern Queensland, having flown from England within 30 days as prescribed by the prize offered by the Australian Government for the first to do so. Hurley joined them on the rest of the flight into Sydney. He was to use this film as the basis of The Ross Smith Flight. However, Hurley needed to show more of journey and cut film and images from his former adventures into Northern Australia, images from Palestine as well as a few fake scenes of cities using postcards held in front of the lens.

Hurley was able to go journeying again in December 1920 when he left on a commission in New Guinea.28 He had dreamed of going to the hot tropics whilst marooned on Elephant Island and had hoped some of his Antarctic expedition friends would join him. But he discovered he was the only one keen and fit to go.

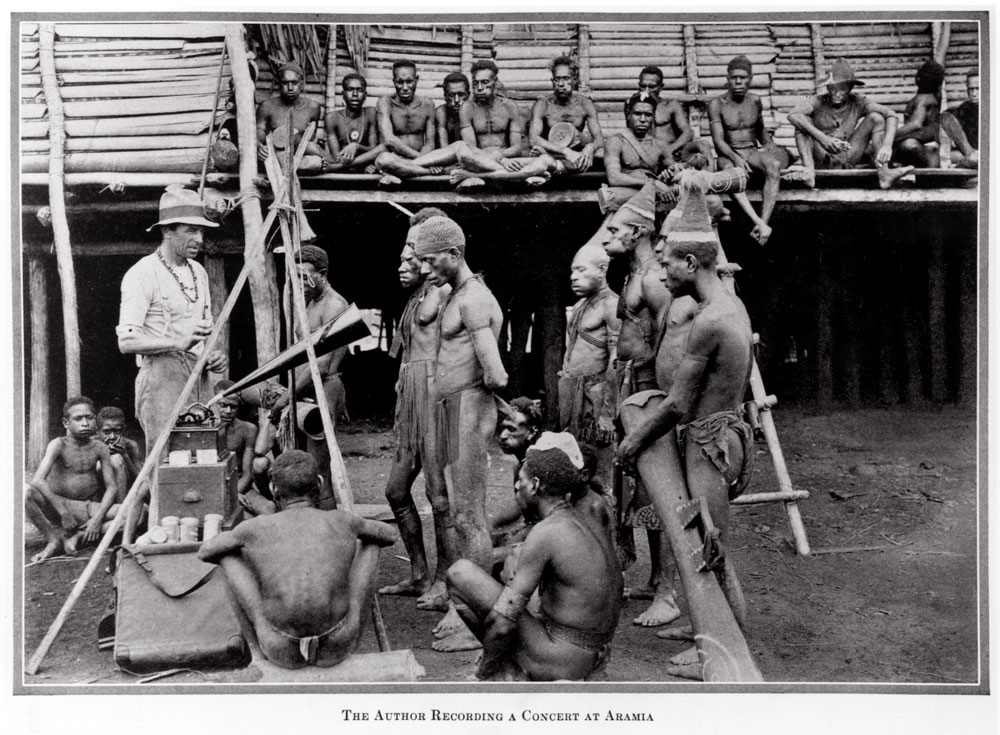

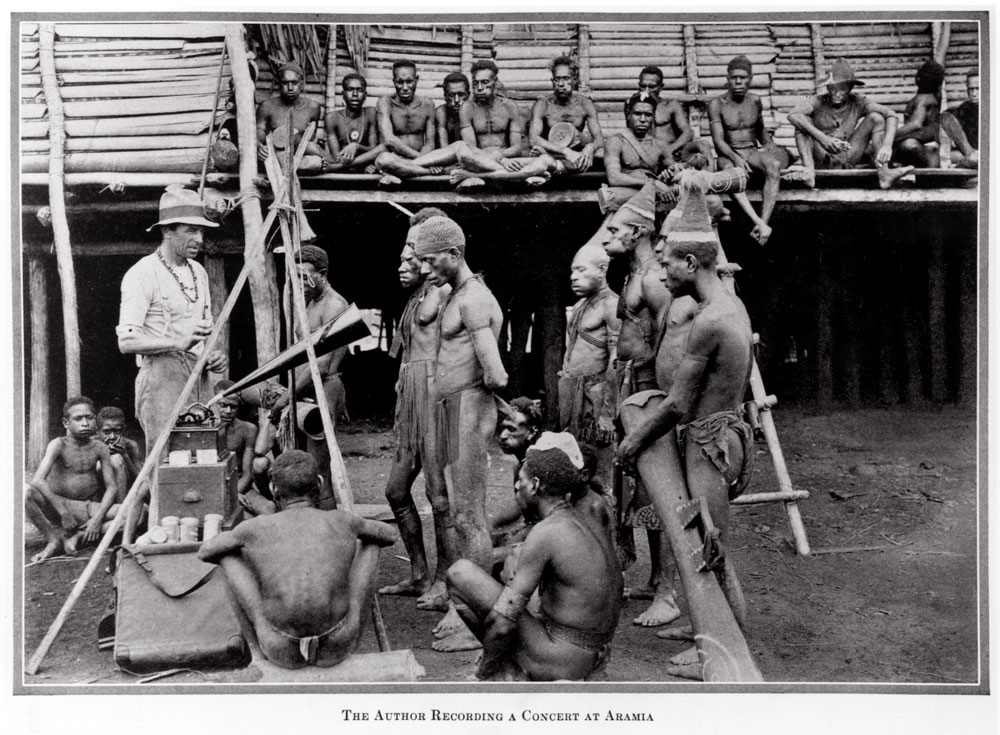

The journey had mixed aims. Firstly Hurley was on a commission for the Anglican Board of Missions, who paid a flat fee for film and slides plus supplied transport and accommodation. They agreed that Hurley would also be free to make his own work while travelling. Hurley set out to make a travelogue.

Hurley energetically pursued both objectives but was not enthusiastic about the missionaries or the natives he met. After much island-hopping around the Torres Strait Islands and a tour of missions along the coast of Papua and along the Opi River, he had completed his contract. His next destination was Yule Island, off the coast of Port Moresby. He then moved from here for a trek into the highlands, a journey he seemed to have enjoyed more as he moved away from the coastal peoples.

Besides filming the people and their land, he also made sound recordings of the tribesmen's songs and dialect.

21 "The Author recoding a concert at Aramia'" Papua New Guinea, 1921

From Frank Hurley's book, Pearls and Savages, 1927

It was while he was returning from the highlands, that he received news of the birth of his next daughter, Yvonne.

The Anglican Board of Missions received their footage, later to be released as The Heart of New Guinea. The film was more of a travelogue than they were expecting with little emphasis on the good works of the faithful missionaries. However, the film was a success with the public.

Back in Sydney Hurley had an exhibition of his Papua-New Guinea photographs at the Kodak gallery in Sydney in December 1921 where his old friend Mallard was now manager, and released his part-travelogue part-ethnographic film as Pearls and Savages.

He also began looking at the Australian landscape visiting the Blue Mountains and going hiking with a friend since 1909, the photographer, Harry Phillips a long term resident. They shared a love of the mountains, and clouds. Phillips had produced numerous scenic books and one on clouds in 1914. Phillips was religious and saw clouds as symbols. 29

Hurley’s next expedition into Papua was to be on his own terms, based on the financial success of the 1922 film, Pearls and Savages. He formed World Picture Exploration, with the specific aim of making travel films. In the first instance he needed more images from Papua in order to pad out the footage he already had.

With some backing from Kodak, the Sun Newspaper and a Sydney businessman, Lebbeus Hordern who supplied two aeroplanes, Hurley readied himself for the next set of challenges. He also learnt to use the new Marconi radio transmitting devices in order to keep in touch. Hurley was keen to see that the expedition was seen as scientific.

On their return to Sydney, Hurley and his team came under fire for the manner in which some specimens had been collected by the Australian Museum representative. The main set of accusations focussed on allegations that material was taken without permission.

Hurley used the new footage and updated his previous success, Pearls and Savages. The new film, With the Headhunters of Unknown Papua, was a popular success praised by the Sun newspaper that had helped sponsor the expedition.

Hurley went off to America for a lecture tour and film showings the film being re-titled The Lost Tribe, largely on account of the Semitic appearance of some of the Lake Murray tribes. The film did not meet with the level of acclaim he had hoped for.

One achievement from the tour through America was that the publisher, George Putnam, moved quickly to record Hurley’s story and publish Pearls and Savages, in a handsome edition in 1924. The book was to be a success. Putnam’s publication of Argonauts of the South was equally successful and appears to have been more popular in sales than other expedition publications. Both books were translated into several languages.

Hurley returned to London in 1924 and took Pearls and Savages on a successful tour and then sold the film to a German company for £1500. His next venture was not so successful. Hurley sold the idea of feature films to the Australian-born British film magnate Sir Oswald Stoll. He set himself up as an independent film studio but found he was refused permission to film in Papua.

The two feature films were made in 1926. The Jungle Woman a melodramatic view of race relations was shot in Dutch New Guinea and Hound of the Deep on Thursday Island. While relatively well received in Australia mainly due to his reputation, the films were viewed as being naïve.

Hurley had made most of his films working as effectively a lone cameraman. The larger and complex feature film production team processes and dealing with actors and crew were not suited to Hurley’s independent temperament. He resolved not to do this type of work again but to stay with featurettes and work as the cameraman for other productions.

He worked as a newspaper picture editor for his long time supporter The Sun in Sydney in 1927 and sold a large number of New Guinea negatives to the Australian Museum in Sydney suggesting that he planned no further projects with indigenous people. Historically Hurley’s films still retain a major role in Australian film history of the period.

Hurley returned again to England, set up in Bushby, the home of the film studios, and obtained some camera work but was unsatisfied. The call came from Mawson for another expedition, so Hurley quickly equipped himself and headed out to join Mawson on the British, Australian and New Zealand Research Expedition arranged to explore and research Australian sovereignty over some of the Antarctica continent.

The two Banzare expeditions resulted in new footage for Hurley but in a lot of frustrations. Hurley’s film, Southward Ho! with Mawson, released in 1930, was another success even though Hurley had been frustrated by the captain’s unwillingness to allow for filming time.

A later film based on the second journey was released in 1931. It was the first Australian full-length feature film to have music, commentary and other sound effects.

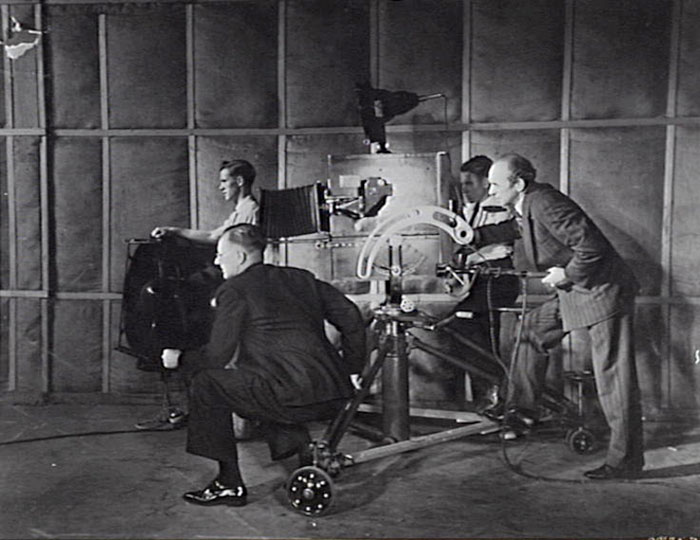

The next eight years were a change of life-style for Hurley as in 1931 he accepted a salaried position with Cinesound, a subsidiary of Greater Union Theatres. This was an opportune move, given that Australia suffered severely during the depression.

Three documentaries quickly followed: Jewel of the Pacific, about Lord Howe Island, Symphony in Steel, about the building of the Sydney Harbor Bridge, and Fire Guardians, about the work of the fire brigades. His work featured prominently in the publications issued during the 150th anniversary of European settlement of Australia in 1938 for which he made the Cinesound documentary A Nation is built.

Hurley then joined the team in the making of the second talkie in Australia, The Squatter’s Daughter, which was being made to follow up on the success of the first Australian talkie, On Our Selection. ‘Cap’ as he was now known at Cinesound, proved his value several times in brokering deals with locals and with his enthusiasm for the perfect picture, despite the number of times it required putting himself, and sometimes others, in danger.

In 1936 however, following success with several documentary films on the power industry, Hurley was placed in charge of a new industrial Film Department which took on commissioned films for corporations and such like. Here his perfectionism did not conflict with the ever more elaborate and fast paced films being made by the company.

Work on other Cinesound films followed including as outdoor cameraman in 1939 for Charles Chauvel’s World War One epic, Forty Thousand Horsemen. For this film Hurley introduced a sunken trench from which the horses were filmed from beneath as they jumped over. The rush and excitement of the sequences in the film remain a classic moment of Australian film history.

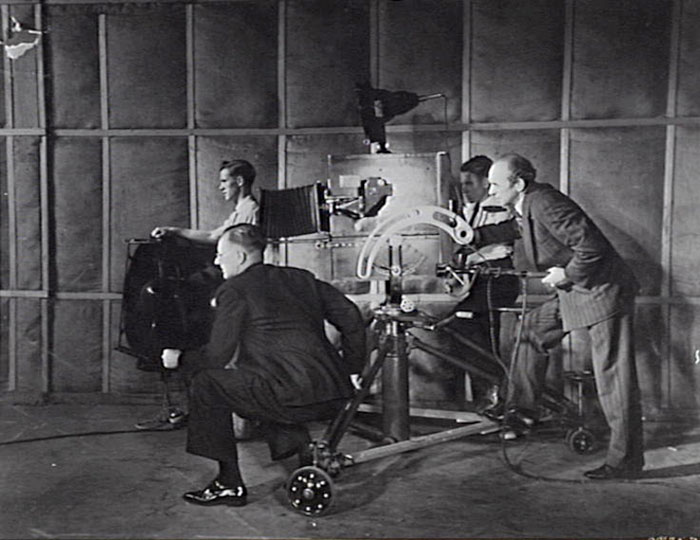

22 Frank Hurley on set working for Cine-Sound Circa 1930s

In mid-life Hurley was relatively settled and his dedication and staying power were still clearly in force. He was known to arrive early on the set, would remain attached to his equipment all day while staying formally dressed and saying little.

He would edit his own work to remove less-than-perfect images and would be often the last to leave the studio or set at night. Hurley also often returned to re-take footage if he was not completely satisfied. He was no longer, however, remembered for his team spirit even if still humorous and quick witted with those he knew well or were important to him. He was rigid in his quest for perfection and unresponsive to the post-war needs of a commercial film and newsreel studio.

23 Frank Hurley with his camera on the Banzare expedition 1929-1930

Taken by R. J. Ross (BP Magazine, 1930)

Despite the frustrations Hurley had with Cinesound and they with his methods, the Hurley name meant a lot to the public and his employers respected his status and abilities. It was thus a surprise and disappointment that, when war was declared in October 1939, Hurley was not approached or given an active role as he expected. His efforts to be posted were rebuffed. It is reported that he was blocked because he was seen as too old at 54.

Hurley seems to have had at least one powerful opponent in Sir Henry Gullett, head of the Department of Information, a still lingering effect perhaps of Charles Bean’s condemnation of his ‘fakes’ in World War One. In 1939 the Prime Minister’s Office added further insult by appointing 23 year old George Silk, an unknown and technically ‘amateur’ photographer from New Zealand, as a war photographer.

Silk won his appointment on the basis of one portfolio of dynamic sailing and skiing pictures taken with the miniature 35mm cameras, not the larger format of conventional news reporters.30 Damien Parer, a young Australian with a passionate interest in the new documentary approach to film had also been appointed.

Hurley was determined to go, and he found a way by being appointed to the national broadcaster the ABC, as a reporter but did not make it past Perth in Western Australia. When Gullett was killed in a plane crash near Canberra, his replacement was Sir Keith Murdoch who knew Hurley and valued his experience. In August 1940, Hurley was appointed to oversee, with a major’s salary, the Official Cinematographic and Photographic Unit in the Middle East.

He would be in charge of the 'young turks'; Parer, Silk, reporter and cameraman Ron Maslyn Williams, and sound engineer, Alan Anderson. Hurley’s brief was to represent the Commonwealth but also the news interests of Cinesound and Fox.

He was soon in the thick of action, chasing the British and Imperial forces during their North Africa offensive against the Italians in December 1940. As each battle progressed, the unit would have to scamper back to Cairo to develop and print as well as to pick new film. This return journey became more difficult as the front moved out, resulting in Hurley becoming very tired of the sand, the dust and the khaki.

Hurley and photographic unit were next moved to Syria, which was for Hurley, a more pleasing landscape than the desert. He was in the wrong zone to capture the action during the June 1941 Syrian Campaign. This was galling as George Silk and Damien Parer obtained good photographs for the news.

In December 1941, the Japanese changed the emphasis for Australia, when Pearl Harbour was bombed and their threat in the Islands of the Pacific brought the war close to Australia's own shores. Some Australian troops were withdrawn along with most of the photographic unit. Silk and Parer went onto make their most famous work in New Guinea.31 Hurley stayed with the 9th Australian Division.

Hurley carried on making small featurettes, which is what he still understood was his brief. He scorned ‘slap-up newsreel stuff’. However the Department and two newsreel companies became more and more frustrated by the lack of relevance of these superbly crafted and picturesque featurettes. His footage of the October 1943 El Alamein allied victory was so badly received that little of it was used.

Hurley, who had been the buoyant team member on his Antarctic voyages, is remembered as a loner in World War Two. While there was much socialising amongst most of the unit, Hurley was rarely found joining in with the others for a meal let alone any other social events. He tended to monitor the younger men and worry about bout their night life. Hurley once recorded in his diary his great satisfaction at a Christmas Day spent developing and attending to chores.

24 Damien Parer, Frank Hurley (rear) Maslyn Williams & George Silk (front)

Middle East Circa1941

Hurley and Parer, who was a devout Catholic, got on well enough. However, Silk, whose forte was action photography and was ambitious and determined, disdained Hurley’s personality, his 'perfect' but static images.32

The gap between what his department and the news reel companies wanted and what Hurley was prepared to produce widened to such an extent that the cost of Hurley’s productions could not be justified any longer. Steps were considered to withdraw Hurley. The difficult question was that no one in Australia knew what to do with this out-of date but well respected cinema and still photographer.

Fortunately, because of his impressive former reputation and connections, he was able to resign from the Australian Army and join the British army on the pay of Lieutenant Colonel as the Director of Army Features and Propaganda in the Middle East. He was awarded an OBE in 1941 for his war work making up a little for the lack of decorations he had received in World War One.

Hurley seemed to enjoy the next forty months, where he had to oversee the work of about fifty different film units as well as having many opportunities to make film and photographs in one area of the world he loved, the Middle east. Cairo became his second home with the reality being that Hurley spent an enormous amount of time on the road, in the field and being hands on with the work, where he was happiest.

'Making a way' after the war...

Hurley, aged 61, returned to Australia in September 1946 after six years away from family and country. All four children had now married and he was a grandfather.

Despite Hurley’s frugal lifestyle and good pay during the war he found his finances were in desperate condition. The fine home in Rose Bay complete with his native gardens and lush lawns, was gone. Mrs Hurley had moved to a semi-detached cottage away from the harbour. Sensing perhaps that he would not have the independence he had enjoyed with his war time films Hurley did not try to find a niche in the rapidly expanding post war travelogue/ documentary or feature film productions. He made one promotional film in 1953, The Eternal Forest as a promotion for the Australian Paper Manufacturers. He was however, far from tired or un-enterprising.

Going Into Print

Taking up again the spirit ‘Unless you're beat your’ bound to win’.

Hurley quickly turned to book publishing, an arena in which he could in a sense continue to serve Australia by promotion of the land instead of its war effort but also make a profit.

He regarded Australia as a magnificent witness to the benefits of white settlement and freedom from the racial and other conflicts which had brought war to Europe and the Pacific.33

He first plumbed his archive. In 1948, Sydney publishers, Angus & Robertson, put out Shackleton’s Argonauts, an edition for a very general readership of his earlier publication on his Antarctic adventures. The book won an Australian book award and was reprinted in 1949 and 1956 (as well as a 1979 edition by McGraw Hill)34.

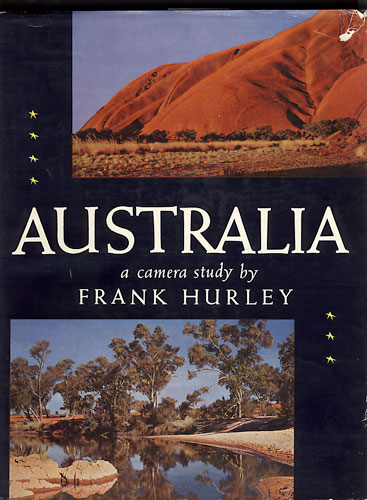

In the same year, he published Sydney: A Camera Study, and in 1949, The Holy City: A Camera Study of Jerusalem and its surroundings. The books, handsome and lavish for the immediate post-war years when rationing still applied, were immediate best sellers. Many were reprinted well into the 1960s.

25 Strathaird passing under Sydney Harbor Bridge Circa 1959

He soon relocated to a series of better homes finally settling at Collaroy Plateau, a rather undeveloped northern Sydney beach area on a large bush acreage with spectacular views, as magnificent as those at Vaucluse. He again set to work on elaborate garden works and built a darkroom in the garage. Throughout the period he also continued with broadcasts on the Australian national radio.

He next set out on journeys across Australia, state by state, most often with costs subsidised with backing from respective state governments and their tourism agencies. He produced a continuous flow of photographic books on Australia’s scenic wonder, cities, rural and heavy industries as well as native flora.35

Flocks of sheep and rustling wheat fields all in bright sunshine were favoured and relatively few city people or Aboriginal people appeared tin what was a domesticated picturesque. The books were exactly in tune with the market and largely without competition. The scenic view catered to a reviving economy, the intensified relationship with the land experienced by soldiers returning and the post-war drive to attract immigrants.

He changed to Sands publishers in 1953 and returned to a craft he knew well from his former life; postcards. He also entered the world of calendars, with his annual output being sought after and popular. The books in colour are crude by later standards but some of the prints of Australian flora (usually from specimens in his own garden) were brilliant in colour fidelity and quality.

Hurley’s output became the popular national and international image of Australia for two decades.

His books were the standard introduction to Australia, found in embassies across the world and on the desk of newly established tourism offices.

In true Hurley style, the Australiana photographs were the result of long and arduous journey to capture that perfect set of pictures.

They were taken with a wide view straight on without low skewed angles favoured by modernist art photography nor the atmosphere of early Pictorialism. This involved yet again much time spent away from home.

He was not above adding in images from former treks into the images he required. For instance, the Palestine sky was to find its place in the background to an Australian scene! The compositions were wide stable and with strong horizontal balance varied with clean vertical elements. Motion was rare and figures posed clumsily. |

|

|

Hurley gave scant attention to the new photographers who had come into fashion from the mid 1920s or the photojournalism of the mid 1930s on.

Whether he bothered to pay a visit to Edward Steichen’s massive 1955 tribute to magazine photojournalism, The Family of Man, when it came to Sydney in 1959 – is unknown. Specialising in landscape and development Hurley would have little interest in the Melbourne Olympics in 1956 but no doubt sold thousands of his Australiana books and cards. His best seller Australia: A Camera Study was released in 1955.

26 Hurley old age pic with dog and wooden model of the Endurance

Hurley was highly active until his death in 1962 aged 78, when he realised that he was dying he refused to be coddled and sat upright in his chair all night. At mid-day the next day, the doctor announced his passing. Mrs. Hurley was left with a generous amount in his will and thus his need to have things in order was satisfied. 36

In 1966 Hurley’s daughter Toni collaborated with Frank Legg on a biography of her father released as Once more on my adventure.

Postscript

Although Hurley’s books continued to be reprinted through the 1960s, a new era of coffee table book came in with American photojournalist Robert Goodman’s lavish colour book The Australians of 1968 which became a huge best-seller.

It was also a time when Hurley’s image of Australia no longer had appeal for a younger audience who turned away to more abstract or personalised art and expressions to reflect a cultural renaissance which would come as the baby-boomer generation came to maturity in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Hurley had an undisputed position in his life time but had missed out on the honours and interest which would start to be awarded to senior Australian cinematographers and photographers still living in the 1980s and 1990s as the appreciation of photography became part of official culture and museum collections.

Recently Hurley‘s name and images have been seen again both internationally in exhibitions and publications on the Endurance expedition and in his homeland, where effort has gone into biographies and exhibitions concerned with Sir Douglas Mawson’s achievements. There had been a growing interest in Hurley's colour work. His post-war Australian pictures too have found new readings.37

Throughout the past decades when no longer in front of the public eye to the same extent as before his death Hurley's work at the various archives holding his work has continued to fascinate researchers. and curators. There are still more publications on Hurley than any other more fashionable senior Australian photographers.

The indexing of the National Library of Australia’s archive of negatives over the 2001-2 period will no doubt reawaken more interest still. Hurley has never been well served by the quality of the reproductions of his work and much remains to be seen of his huge output.

Some of the modern critiques would no doubt be thoroughly bewilder Hurley but surely he would be pleased in the renewed national and international interest in his work 75 odd years since launched his books in New York. He might say the Argonauts are back.

27 Cavern carved by the sea in an ice wall near Commonwealth Bay, 1911-1914

Footnotes

- Hurley’s book was similar to The Great White South (London, Duckworth, 1921) by Herbert G. Ponting on his work as official photographer to the British Antarctic Expedition (1910-1913). Hurley met Ponting in London in early December and attended the latter’s illustrated talks – and admired his work and splendid patter. Hurley’s own showmanship was already formed but probably heightened by seeing his British contemporary at work. Hurley did not give talks in London on the Shackleton expedition and was soon off to South Georgia to shoot extra footage of the natural life for the Endurance film. Hurley’s earlier Mawson expedition footage edited and released in the United Kingdom under the title Life in the Antarctic was possibly shown in London by Dr Mawson as he was there at the time.

- Film and photography history are quite separated disciplines and equal skill in both is rarely to be found in one author and certainly not this one. Hurley has a major place in Australian film history, see the Australian Film Institute bibliography ww.cinemedia.net/AFI/biblioz/hurl_bib.html. See also film maker, Martha Ansara’s excellent article, ’A Few Words about Frank Hurley’, Metro115, 1998, pp.35-42.

- Shane Murphy’s 1995 video tape of his interviews with Toni and Adelie Hurley is held by the Mitchell Library, Sydney and Martha Ansara’s taped interview from 1995 is held by the ScreenSound Australia archive in Canberra www.screensound.gov.au.

- Published in 1789, the poem remains a school room favourite. For the impact of polar exploration in literature and popular culture see Francis Spufford, I May be Some Time, Faber and Faber, London, 1996.

- The earliest short biographical references are in ‘Frank Hurley, Photographer’, The Lone Hand, November 2, 1914, p. 404, seemingly with information direct from Hurley, where his age is given as 27, giving a birth in 1887. The article has his professional career beginning in 1906. Putnam’s foreword to Pearls and Savages has Hurley aged 34 giving a birth in 1890. The 1890 birth date was repeated by Jack Cato’s Story of the Camera in Australia, (1955), reprinted 1977, Institute of Australian Photographers/ Methuen, 1977, in Hurley’s lifetime and then through most later published references until 1966 when Frank Legg and Toni Hurley biography, Once more on my adventure, was published (Ure Smith, Sydney).

- Although from the 1880s schooling was compulsory but regular attendance not stringent, absences were common, most children left school at 13-14 to enter the work force. Secondary or superior years of high school were not the norm. Hurley would have been due to leave around this age. Early school departure is also quite common in photographer’s biographies, given the trade status of the medium, until recent times.

- Argonauts of the South, p.9. Hurley senior’s motto was shared with taken from a rousing poem read in schools at the turn of the century. The elderly Labour politician, J.T. Lang could still recite the stanza when interviewed in 1973:

- It was a noble Roman, in Rome’s Imperial day,

- Who heard the coward croaker before the castle say,

- “They’re safe in such a castle, I see no way to take it”.

- ‘On, on!’ exclaimed the hero, ‘I’ll find a way or make it!’

- see Wendy Lowenstein, Weevils in the flour, an oral record of the 1930s depression in Australia, (1978) Scribe, Melbourne, 20th anniversary edition, 1998, p.91.

- Hurley’s daughter Toni found an early diary after her father’s death with these words written in it. Cited in Leonard Bickel, In Search of Frank Hurley, Macmillan, Sydney, 1980, p.13.

- A group of five dramatic train pictures were reproduced in The Lone Hand January 2 1911, pp.187-191.

- J.F. Hurley, ‘Night Photography’, Australasian Photo-Review, March 22, 1909, pp. 131-2,143, 185, 237; ‘Photographing Locomotives’, January 1911, pp.10-13, 19, 23.

- Captain Frank Hurley, Argonauts of the South, Putnam, New York, 1925, p.11.

- Mawson ‘s comments in an article in a magazine called Life, 1 September 1919, pp.161-7, apparently confirm Hurley’s account of the train stunt. The most thorough and comprehensive perspective on Hurley the man and his career was done by David P. Millar. for his book, From Snowdrift to shellfire: Capt. James Francis (Frank) Hurley 1885-1962, David Ell Press, Sydney, 1984. Miller checked sources but where evidence was lacking pointed to Hurley’s own tendency to embellish and contract events in telling his life story.

- For a description of his equipment and methods in the Antarctic, see ‘Frank Hurley Official Photographer to the Mawson Expedition’, Australasian Photo-Review, March 23, 1914, p.129-130.

- Henri Mallard’s role first appears documented in a the chapter on Hurley in Jack Cato, The Story of the Camera in Australia, Georgian House, Melbourne, 1955 on p.138. Cato describes the elderly Hurley’s appearance and manner so seems to have interviewed him sometime in the late 1940s early 1950s. Cato presumably checked his text with Hurley before publication. A taped reminiscence by Mallard in the Film Australia archive, Sydney, has the same story. However, Mallard may also be embellishing history. Hurley claimed in 1927 at the Australian Royal Commission on the Moving Picture Industry that his cinematography began in 1910 with footage of the Burrinjuck Dam in New South Wales

- Later, after the War, Hurley was part of a successful campaign against the lease owners that resulted in the Tasmanian Government declaring the island a sanctuary.

- The negatives may be in the National Library of Australia Hurley archive; a few large carbon prints were in the collection of Dr Mawson’s family in 1996 and had been included in exhibitions alongside the Expedition images..

- Douglas Mawson’s archive was placed with the University of Adelaide after his death in 1958 but later languished over the next decade. The collection is now under active care and promotion by the Mawson Antarctic Collection, Waite Campus. Further books and exhibitions on Mawson and the Australasian Antarctic Expedition are planned.

- For the English advertisements for the Endurance expedition cited on Nova Online: Shackleton’s Antarctic Odyssey, www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/shackleton which also gives detail of a new documentary film on the Endurance expedition.

- In an article ‘Frank Hurley, Photographer’, Lone Hand November 2, 1914, p.404, it is reported that ’Hurley had no sooner returned to Sydney [with Birtles] than he cabled an application to Sir Ernest Shackleton for the post of photographer to his expedition and says he was appointed at once, but when war broke out he assumed that he trip would be off. An article in The Sydney Morning Herald, March 6, 1914, indicated he had applied and been accepted sight unseen based on the quality of his Mawson films. As Hurley returns with Birtles in August and War was declared on 1 August and the British order for general mobilization was on August 4, Shackleton received word he could proceed by August 8 and did so from Plymouth that day, there can have been too little time for Hurley to find out after his return from the north. He possible received the acceptance and departure date en route – details from Caroline Alexander, The Endurance: Shackleton’s Legendary Antarctic Expedition, Bloomsbury, London, 1998, pp.10-11. It is possible he had already applied after his return from the Antarctic but went on the Birtles trip assuming the expedition was off. . For details of Hurley’s Endurance diaries see American researcher, Shane Murphy’s site dedicated to Shackleton’s photographer, at www.frankhurley.com and his CD Rom publication Shackleton’s Photographer: Frank Hurley’s Diaries 1914-1917.

- See www.frankhurley.com.

- Bean and Hurley’s differing approach to verisimilitude is discussed at length by Martyn Jolly in ‘Australian First-World War Photography: Frank Hurley and Charles Bean’, History of Photography, vol.23, no.2 Summer 1999, pp.141-148. Jolly, Head of Photomedia, Canberra School of Art, Australian National University, is undertaking a Ph.d on Hurley and WWI photography.

- Hurley’s relationship to the Australian soldiers response to being in the Holy Land is discussed by Robert Deane, ‘Australian military photography, WW!-II Frank Hurley to George Silk, paper presented at the Revealing the Holy Land seminar, National Gallery of Australia April, 31, 2000. See www.nga.gov.au

- Little is known of Antoinette’s background. She has left no memoir of her life with Frank. She was stylish, sociable and cultured by comparison with Hurley. Her family do not seem to have visited or been in contact much. She would have found Sydney in the immediate post-war years a very different environment. To be the mother of twins soon after her arrival in a foreign land with no friends or family would have difficult.

- Jolly, Martyn, ‘Australian First-World War Photography: Frank Hurley and Charles Bean, History of Photography, vol.23, no.2, Summer, 1999, p.145.

- The complex history of Hurley in Papua New Guinea is documented in James Specht and John Fields, Frank Hurley in Papua: Photographs of the 1920-1923 Expeditions, Robert Brown and Australian Museum Trust, Sydney, 1984.

- See Philip Kay, The Far-Famed Blue Mountains of Harry Phillips, Megalong Book, Second Back Row Press, Leura, NSW, 1985. Phillips may have had considerable influence on Hurley’s own later productions of scenic books.

- See Peter Brune and Neil McDonald, 200 shots; Damien Parer and George Silk and the Australians at War in New Guinea, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 199?.

- See Gael Newton, Going to extremes George Silk photojournalist, exhibition brochure, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2000.

- See Julian Thomas’s discussion ‘The Best Country in the World’ in his The Showman: The Photography of Frank Hurley, National Library of Australia, Canberra 1990

- Their respective forewords are revealing; Hurley’s reflects the post-war consumerism and focus on development in Australia by stressing the economic potential of the Australian controlled Antarctic territory. The heroic years of scientific expeditions seem far gone. The 1979 edition however, has a forward from Philip Law stressing that conservation was a primarily responsibility.

- The National Library of Australia bought Hurley’s papers and negative archive from Mrs Hurley in 1965. The thousands of negatives and transparencies are being indexed and digitized for publication on the web site in 2002.

- John Thompson, Hurley’s Australia, Myth, Dream, Reality, National Library of Australia, Canberra, 1999. Hurley projects have been done by Richard Ferguson formerly of the University of Adelaide, research and cataloguing proceeds at the Mawson Research Centre at the University of Adelaide and as well research and exhibition work by Martyn Jolly and Dr Erika Esau at the Australian National University and curators at the Australian War Memorial. In recent years both Jungle Woman and Pearls and Savages films have been restored and represented complete with original music and commentaries.

|